NEWICKS TRIMARANS

1962 I chose to live in a small boat, Blekingsekan 4.75 meter long about 15’ 6’’.

The idea was a floating home that could bee moved between ports in good weather. As usual my ambitions grew and I did not always have patience to wait for good weather. That made me realize that a better and more seaworthy design would be desirable. Since then I have been reading, thinking, and experimenting about and with small boats. I have made much progress but I am still searching.

I had spent the summer of 1962 among the islands in the Bohuslän archipelago. When autumn came I sailed south to Copenhagen. I found a nice docking space outside a Baltic trader in Christianhavns Kanal. At that time everything was relaxed and there was no mooring fees.

Copenhagen had excellent libraries among them an obscure one named Sjöfartens Bibliotek, Seafarers Library. It was situated in Nyhavn.

A brass plate on a door with its name and opening hours lead me by chance into a reading room filled with books. The few tables it contained were unoccupied. The room was empty and continued to be so for the following months that I daily visited it.

I started to look at the titles. Canoes of Oceania by Haddon & Hornell, The Junks and Sampans of the Yangtze, by G. R. G. Worcester, fascinating stuff for a 23-year-old person who wanted to learn about the sea. There were also the publications of the Amateur Yacht Research Society. It was the avant-garde of those days. Their publications was about multihulls, self-steering for sailing yachts, hydrofoils, different rigs, wind tunnels and test tanks, it was run by Dr. John Morwood.

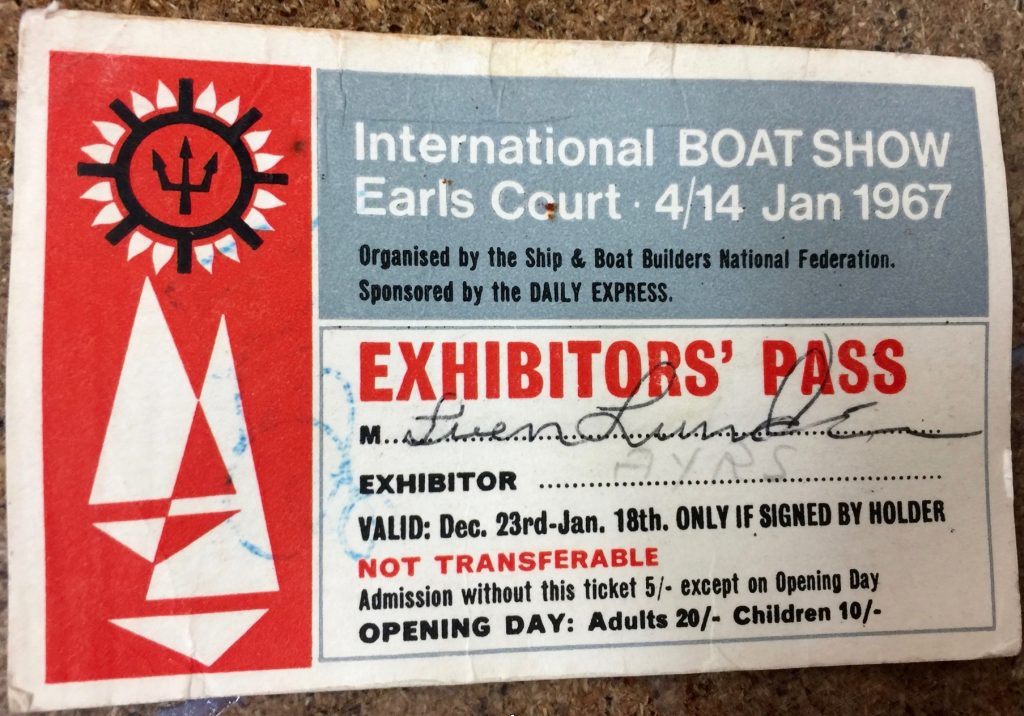

To get a deeper understanding of it I thought myself mathematics. Being a dyslectic I was unable to get a degree. That did not interfere with my ability to learn and understand mathematics. A bonus was that teachers of mathematics were an article in short supply those days so got a job despite my lack of formal qualifications. The other teachers complained about being underpaid. For me who for many years had been living on crumbs and thin air it was good salary. I got plenty of money. I became a member of the Amateur Yacht Research Society I began a correspondence with its members and was invited to man their stand at the London boat show.

Manning the stand, talking to other members and explaining to the public educated me. There were also plenty of bookshops in London. I bought lots of nautical books. It filled four big boxes. It was heavy about 50 kilos but the thought about all the wonderful books gave me such unbelievable strength that I was able to bring them with me to Sweden. English books in Sweden at that time was twice the local price and delivery time was six weeks.

USA

In May 1975 my diligence had born fruit. I had built a series of more and more seaworthy boats and made a number of ocean passages, but I was still searching for more knowledge. That May in wonderful weather, I docked in Goat Island Marina, Newport R.I., it was run by Peter Dunning. It was also the finish of the OSTAR.

OSTAR, when inaugurated in 1960, it was the first single-handed ocean yacht race; it is run from Plymouth to the United States, and is held every four years. Amateur Yacht Research Society had made many contributions to the boats racing in it. Peter Dunning knew plenty of famous single-handed sailors, like Chichester, Tabarly, having had them as guest at his marina. Also he liked single-handed sailors including me. He helped me a lot.

One day it was a knock on my hull. It was Tom Follett who had made a sensation by coming third in the 1968 race in Cheers a Dick Newick proa. I had read about Tom not only in the Amateur Yacht Research Society’s publication and in Dick and Toms book: Project Cheers: a new concept in boat design. It was like meeting a hero. Tom was very interested in my boat Bris and my voyage – Reed more about Bris, under “my boats”.

Her construction was cold molded.

Cold molded hulls have been built since the technique was used for World War II planes. I had used resorcinol glue. Unlike epoxy, it does not have gap filling properties. That required the joints to be close fitting and clamped under pressure to achieve good results. Today I use NM-epoxy exclusively, benefiting from its superior bonding, gap-filling, strength and water resistance.

The method requires a substantial framework with close-spaced longitudinal stringers laid up over a number of transverse frames. Although there are a lot of wood parts involved, there is generally not too much fairing required if the transverse frames are accurately cut to the right outline to allow for the stringer thickness.

It was not very difficult but it took time because of all the pieces.

Always keeping my eyes open I had learnt the method 1968 when I was moored with Anna at Souter’s boatyard in West Cowes, Isle of Wight. The people there were very kind to me and thought me all I needed to know to build a boat using that method. At that time it was the state of the art.

After showing Tom my boat and telling him about my voyage he left. People in Newport were very friendly to me and got invited to plenty of parties.

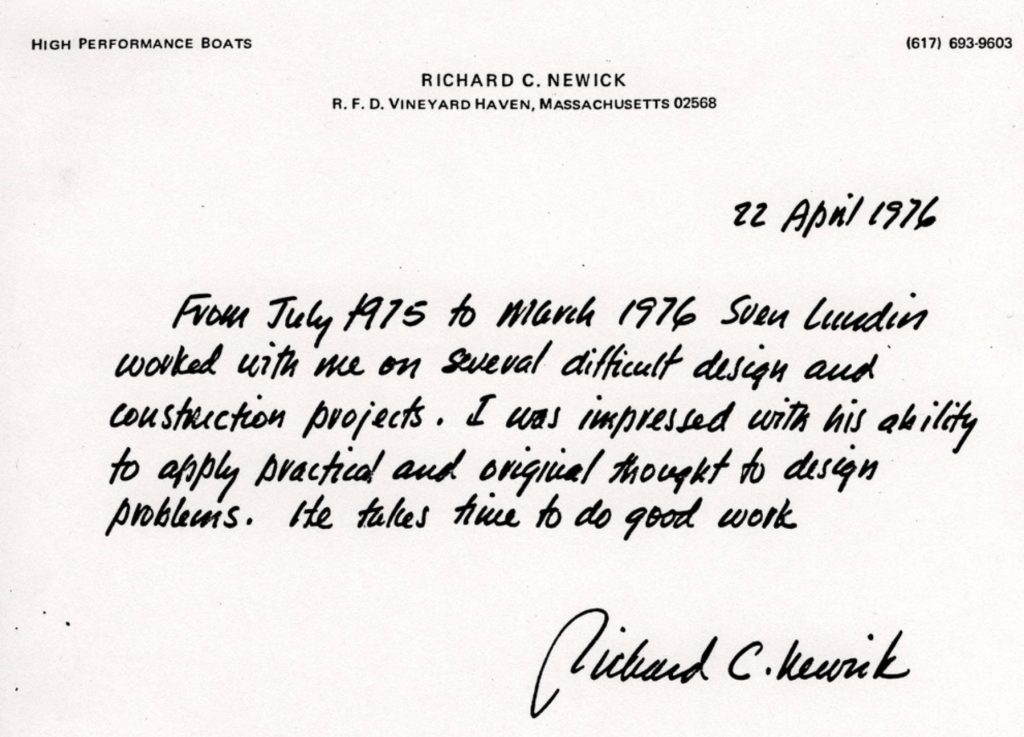

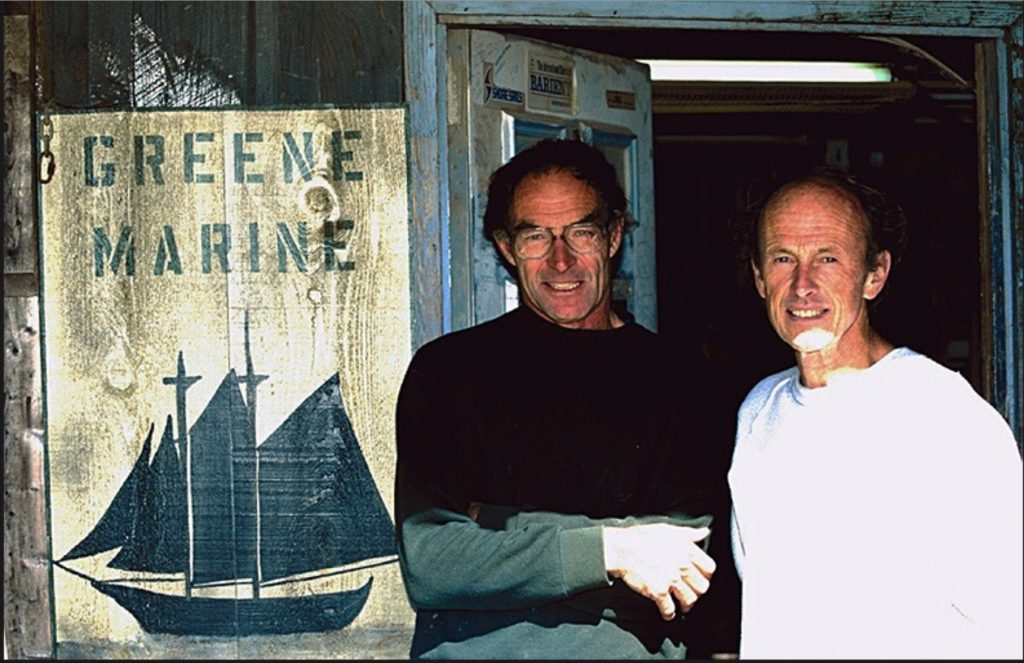

At one party not long after I met Dick Newick the famous trimaran designer. I was in awe. Dick asked me about my voyage and boat. Then he asked if I liked to come and work for him. It was a rare opportunity. I said yes immediately. Dick lived on Martha’s Vineyard an island south of Cape Cod in Massachusetts known for being an affluent summer colony. It was a fifty-mile sail from Newport. I left in a hurry. Peter Dunning ask why the hurry. For me the search for knowledge was the driving force. I told Peter so but of course people do not understand a seekers passion.

I anchored up in Vineyard Haven next to Dick’s trimaran Tricia. Dick picked me up in his Land Rover and drove me to his house he had designed and built himself. Nailed to a tree was a sign: “Beware of proa constructor”

I had expected a big office with several employees, but it was only Dick. The main occupants of the house were Dick’s wife and his two daughters.

-

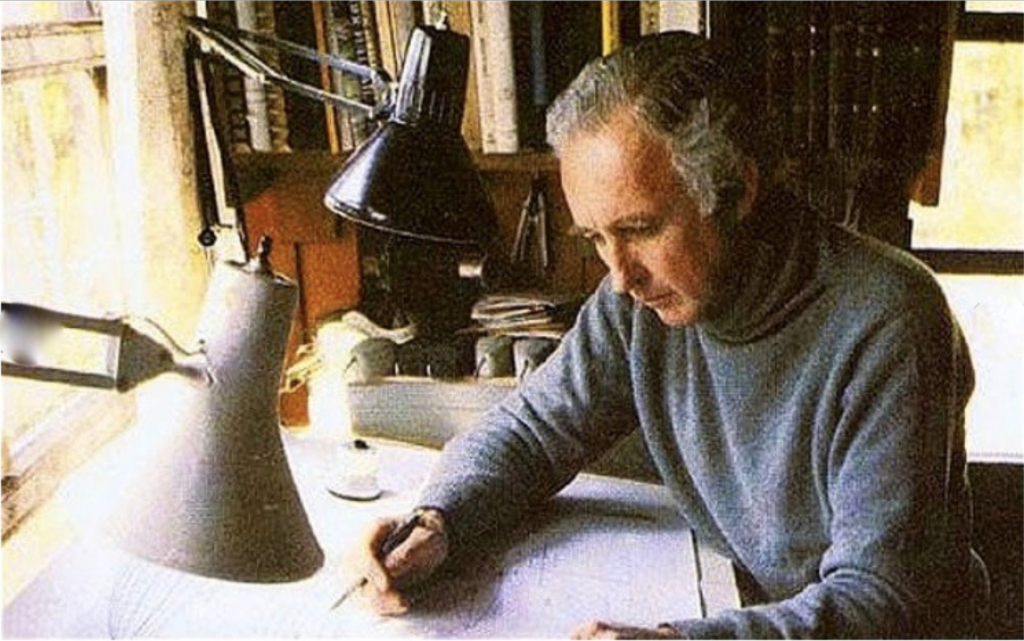

Dick at his drawing board. His work space did not really have place for more than one person, may be the room had an area of at most 3-4 sq. meter. Dick did not seam to mind that his beautiful wife occupied most of the house. One of his favorite books was. Small Is Beautiful: Economics as If People Mattered by E. F. Schumacher

This point in time coincided with the consequences of the 1973 oil crises. People had begun to realize that there was limits the earth’s resources.

Dick had charter business in St Croix, Virgin Islands. Due to racial tensions he had moved up to Martha’s Vineyard. To get a new income the idea was to start a boatbuilding business making trimarans. Dick believed that his trimarans where superior to everything and had a great future. Time has proven him right. They definitely were very fast and that was what Dick liked. Fast is fun, was his slogan.

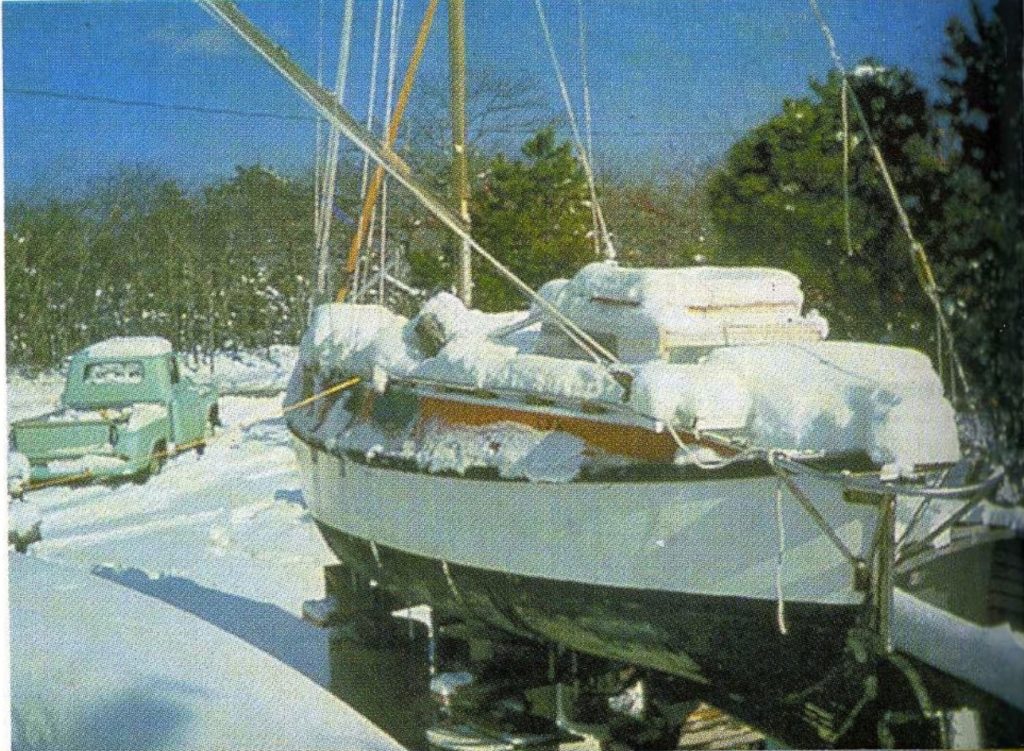

It was to help building these boats that I was there. Tom Follett had told Dick that I was a good boat builder. Dick had orders for three of his 31 feet Val designs. The idea was that they would pay for the tooling.

Dick had not much money but he had found what he called two pot-smoking hippies Rory and Ovid, who had a workshop in a dilapidated unheated metal building. It used to be a lorry garage. The building was hot in summer cold in winter. It had no ventilation, not ideal for glass fiber work.

When I arrived the tooling for the hulls was done, a big step, but multihulls are complicated boats and much was lacking. Despite smoking pot Rory and Ovid were smart boys. They both came from well to do families and had ambitions for their small company, which they called Daffy Duck Marine. Ovid had worked in Detroit designing cars.

The idea was that I was going to be Dick’s helper. It was so arranged that Dick was to pick me up in his Land Rover at ten AM and then we do whatever was needed to do that day. It was very varied. Sometimes we worked with Rory and Ovid sometimes in Dicks tent in his garden sometimes we drove over to the mainland and did errands, like to Boston to get supplies for sail making from Bainbridge or to Edey & Duff in Mattapoisett to pick Peters brain.

Luckily I was able to contribute with something right at the beginning. That way I made a good first impression. As I said the hulls were done and now work had commenced on the deck of the main hull. A circular fore hatch was going to be constructed just in front of the mast. I suggested that they made it elliptical instead, arguing that that way they it was possible to take the hatch below when not in place. I also showed how to construct an ellipse with the help of a piece of string and two nails – there is also the rectangle method, the concentric circles method, the trammel method and more.

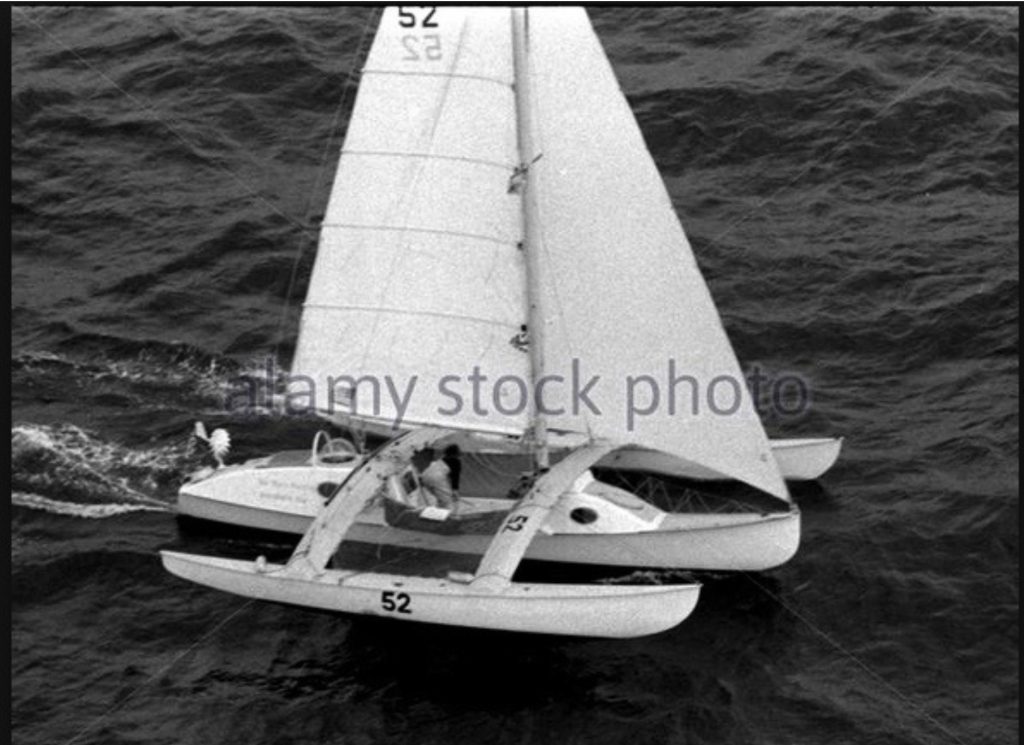

The Val class was really a very minimal boat, very clean and neat. Dick did understand that a boats speed was the ratio between power and resistance. He always tried to reduce the resistance as much as possible to get a small light design.

The cross arms – Dick always used Polynesian terms like amas and akas, but being dyslectic that is to hard for me – did a lot of resistance especially when at high speed they hit waves. Dick’s novel idea was to make them crocked and attach them high up on the main hull.

Working in Dicks tent to make the tooling we became the “Swedish – American crocked beam company”. Now I started to learn. Dick had a barrel of something he called epoxy. That was new to me.

“How can you have been living without epoxy”, Dick asked? After a while I began to ask myself the same question. Epoxy is amazing stuff. Then there was carbon fiber and Kevlar.

Those were the early days of multihulls and they were not common. Now and then would be customers came to the island to test sail Tricia. Dick always brought me along as crew. According to Dick:

“People sail for fun and no one has yet convinced me that it’s more fun to go slow than it is to go fast.”

At that time Tricia was one of the fastest sailboats afloat, for shore, many people like speed, but it has its price and not every one of his customer likes to beat to windward at eighteen knots with spray flying everywhere. Dick was so excited that he did not notice it, but most of them had come for speed and was happy. Thanks to Dick I got a lot of trimaran sailing experience.

One of Dicks customer was Harry Morss, a graduate of Harvard and MIT. Harry was also a member of the prestigious New York Yacht Club. Harry chartered Tricia for a New York Yacht Club meeting. He needed a crew. Dick was disqualified because it would be crashing the party, he said. We sailed to Marbelhead where the meeting was. In New England fog is very common due to the cold Labrador Current meeting the warm Gulf Stream. Shore enough sailing south from Marbelhead after the meeting we encountered fog. We were headed for the entrance to the Cap Cod Canal. Harry did the navigation. Sven, he said. Go up front and keep a sharp lookout forward, in 17 minutes you should see a buoy. After 17 minutes I saw the buoy. After a few more buoys, which were spot on, I had to look for the entrance to the canal. When the time had passed. Harry asked, “Do you see the entrance?” I thought maybe his voice was a bit worried.

“No”, I said.

“It should be here”, he said.

At that time I saw a breakwater on each side of the boat. We were right between them. The distance between them is only 260 meter or 0.14 of a nautical mile. This was long before GPS, not only that strong tidal currents have to be taken into account. It was amazing to witness such accurate dead reckoning navigation. After spending a night in Mattapoisett we sailed through Woods Hole that has a very strong current. We picked up Dicks mooring after successful voyage.

It had been an interesting time discussing boats. Harry had written the book: Design for fast sailing, published by The Amateur Yacht Research Society. The one thing that was on our minds was OSTAR 1976, the singlehanded transatlantic race that finished in Newport at Goat Island Marina. Even I had planned to do the race. My boat was much too small but Peter Dunning had written to the race committee and I had been accepted. Six of Dick’s boats were entered four of them Val’s.

Rory Nugent entered one Tom Ryan who lived in Boston came down every weekend to work on one Hamilton Ferris had one. Mike Birch from Canada had ordered one. I had met Mike in Madeira 1973 when he delivered a boat. I had rowed over to the newly arrived boat and asked if he did not have any cans of food that had not been eaten during the delivery. He kindly gave me some. That kept my stomach happy for a few days. Now he was delivering a car from Florida to Boston to save the fare. Walter Greene was also there, but just to get the tree hulls. He would do the rest himself with his wife. Walter was a good racer and had worked for Ted Hood. He knew what he was doing. Phil Weld a rich man owner of the Boston Globe newspaper had a big sixty footer built elsewhere. I had met him earlier in Martinique.

There was also Mike McMullen an Englishman that had bought Three Cheers a trimaran Dick had built in St Croix and Tom Follett had sailed in the 1972 race. Unlike Cheers Tom could not get the boat to self-steer and this was the time before electrical autopilots. Tom finished fifth which was very good, but with an autopilot he would have won.

In order to get to Plymouth for the OSTAR race I left the island in March. It’s not the ideal time to cross the northern North Atlantic in regards to comfort. Regarding safety I had complete confidence in my small vessel. She had survived a lot of storms in the Southern Ocean during my attempt to round Cape Horn from east to west. After that I had made a lot of improvements to her during my stay at Daffy Duck Marine, based on my experience with heavy weather.

Already the first day out the Atlantic a gale came up and capsized us on the shallow waters of Georges Bank. It was cold. Bris had of course no heating, but I continued. I was in Plymouth in good time for the race, but the capsize had made me change my mind. I decided to sail back to Sweden and start a new boat from square one.

TRIMARANS GOOD AND BAD

If you count Walter Greene’s boat Dick had seven very fast boats in the race and he had great hopes, but all did not go well.

The flagship, Phil Welds Gulfstreamer flipper in the Gulf Stream. Phil and his crew spent four days inside the up and down turned boat before a passing ship rescued them. Now there were six left. Next Hamilton Ferris Val was capsized. Also he was rescued. Tom Ryan made it to the start but did not finish the race. I do not know why.

Mike McMullen in Three Cheers was a big hope. Mike had an electric autopilot and had sorted out most of the problems Tom Follett had encountered four years before. The day before the race he lost his wife Lizzie. She was helping him to clean the bottom of the boat with an electric sander. The tide was coming back. She was standing in salt water up to her knees. Salt water is an excellent conductor. She was well grounded when she dropped the electric sander she was using. She was electrocuted when she bent down to pick it up. Mike kept a brave face. I watched as Mike smiled and waved to the crowd on his way out to the start the next day. Mike and Three Cheers disappeared somewhere in the North Atlantic Ocean.

Four of seven of Dick’s trimarans did not make it. Mike Birch finished just behind Eric Tabarly’s 73-foot ketch and Alain Coals 276-foot four-masted schooner Club Mediteranee. It had been a very stormy race that favored the big monohulls therefore all the more surprising.

Mike and Walter had become great friends. Walter had built an other trimaran in his garage, Acapella. Now there was an other race in France the first Route du Rhum 1978 St Malo to Guadeloupe. They decided Mike should enter in Acapella and if he did win they should split the money. Michel Malinovski in Kriter V a 21 meters long monohulls was the favorite. People did not think much of the small Acapella and the quit Mike Birch.

At that time there was no tracking so when Michel and Mike did see each other near the finish line it was very exciting. Malinovski was in the lead and then suddenly a strong gust came down from the mountain. The monohull heeled right over and lost speed; the trimaran on the other hand took off like bullet. Mike did win by 98 seconds. It was a sensation.

THOUGHTS 40 YEARS LATER

Dick was disappointed that after all he thought me I never converted to a multihull sailor. 1975 multihull designers were rebels against the establishment. That has changed completely nowadays-even America Cup races are done in multihulls. I learnt there are many ways to sail but what is important is to clearly define the requested capabilities. Speed is the most expensive item. Of course, when racing nothing else counts. I sail for other reasons. If your boat is not so fast that it can sail away from storms you better make her seaworthy instead if you like to survive, luckily that is neither difficult nor expensive assuming you have a small boat.

Speed is the most expensive item. I have chosen to let slowness pay for desirable properties other than speed. Modern man does not encourage cruising at leisure, as I wander our oceans I ignore that. The year at Martha’s Vineyard gave me friends like, besides Dick, Mike Birch, Walter Greene, Nigel Irens and others in the multihull community.