JAPAN RO =YULOH

I have always liked sculling. As a child on the island we considered rowing being for the birds.

Growing up and getting a utilitarian perspective as captain of a small, decked cruiser has only reinforced that view.

To propel a small, decked cruiser with one oar sticking out of the boats back certainly is handy. Two oars sticking out from the sides of a boat definitely is cumbersome navigating restricted waters.

Two oars sticking out from the sides of a boat is also cumbersome when the wind comes is gusts, no wind then a bit, then no wind again. When no wind, scull when wind sail, the one method of propulsion does not interfere with the other.

1962 was the year I seriously started to study many different aspects of water transport. I read about boats in Oceania, India China from present time back so far as recorded history. I came across the Chinese yuloh.

The yuloh I realized was definitely superior to the western sculling on two important ways.

First, thanks to its lanyard no force is needed to counter the forward producing force. If there is no forward producing force the boat will not move forward so it’s a force of no little importance.

The propeller of a motorboat produces a forward force. That force must be transmitted to the boat. That’s what the thrust bearing does. The oar transmits the forward force to the transom and in the case of western sculling to man. In the orient the lanyard does that job, a bit like carrying a load or transporting it in a wheelbarrow. The wheel does part of carrying.

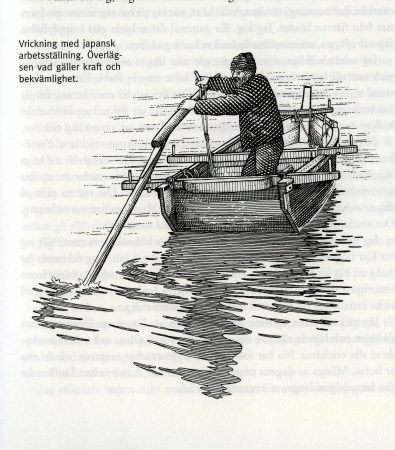

The second advantage is that using the yuloh you are standing sideways in the boat and can in addition to your arm muscles use the leg muscles to put the weight of your body on the oar. That process is also much better ergonomically. It helps to prevent repetitive strain injuries and other musculoskeletal disorders.

I was fascinated. So many advantages! Why did we not use it? What was the catch? Thousands of European seamen had in the days of the square riggers been to China and been transported from the anchorages in sampans propelled by just yuloh’s to the shore. Why had we not copied the clever Chinese and Japanese watermen?

I did some experiments but did not get it right. There where many other things that occupied my mind. Finally 1988 in Amfibie-Bris I made a version that worked very well. 1989 in the rivers of Brittany I used it successfully as well as later the same year in New England after having crossed the northern North Atlantic from Ireland to Newfoundland.

Some time passed again. 1997 I decided to find out how it was done in East Asia.

I chose Japan, despite a guidebook stating it was the most expensive country in the world, and that the language was one of the most difficult in the world.

Not spending money in a expensive country or cheap or not being able to speak an easy language or difficult makes not much difference I decided.

In the 50-s and 60-s I had done a lot of hitch-hiking, so not having much money I decided to try that again. In a small backpack I put a sleeping bag a bivaque, bred and water. Full it weighed 5 kilo.

I phoned the Japanese embassy in Stockholm asking where in Japan would be the best place to study this ingenious, labor saving gadget. The woman who answered sounded offended.

“Japan is a modern country” she said a bit offended.

That was not much help, but with the guidebooks help I decided that northeast Japan would be my best bet.

I bought a ticket to Narita Tokyo.

At the airport I got a free roadmap of Japan. Before moving it’s a good thing to spend time choosing the right direction. A big city is a hitchhikers nightmare and Tokyo was close. After studying the map for two hours I had found a route bypassing the big city.

The hitchhiking went well. I ate of my bread, I drank of my water, and I slept outside. People were very friendly. I visited small ports but like the lady at the embassy had told me I did not see any yuloh.

Towards the evening of the third day I got a ride with a man who told me he was a police officer.

As we neared Kesennuma and the end of the ride he asked me if I liked to visit the police station. I sure did.

When my friend presented me everyone politely stood up.

They kept standing up for maybe half an hour before, one by one they went back to work.

There where not many westerners in that part of Japan and the policemen where curios as to my business.

I was well prepared. I had read that patience and calmness is appreciated in Japan. That suited me fine. I am by nature calm and have plenty of patience. Now I made an effort to be even more calm and patient.

I also had a picture of me sculling a boat and a picture of a yuloh. I showed them my pictures and said that I like to study the Japanese yuloh.

They did not understand a thing that for me was so obvious, how could anyone not be interested in the yuloh.

They were patient I was patient. Time passed. They phoned friends, plenty of people got engaged. Finally after about two hours they understood and my friend told me, tomorrow you will scull with an Japanese yuloh, but it is a very narrow and winding road so we drive you there in a police car. Tonight there will be much rain so you sleep here. Maybe here will be much noise, that’s because it’s a police station.

Now we go to a sushi bar. At the sushi bar suddenly they spoke much better English. They had studied English for many years, but never before spoken it.

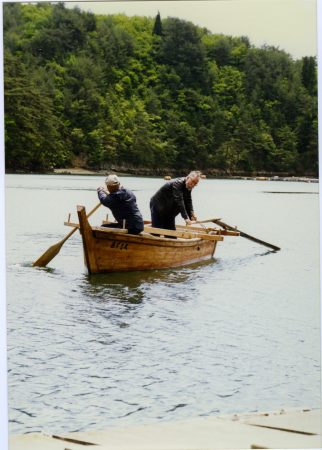

Next morning two policemen drove me the narrow winding road to Nishi-Mohne, just a small village with an oyster farm run by Shigeatsu Hatakeyama and his family. It was Saturday so one of the sons studying at the university was at home, that was luck because he spoke some English.

It turned out that Hatakeyama was a famous environmentalist. He had the idea that the forest influenced the oysters. He and his fishermen friend had for many years gone to the mountain and replanted it after deforestation because in the autumn when the leafs fell to the ground the produced an acid that brought iron to the rivers flowing to the sea, and without iron no good oysters could grow. Now he had with the help of a traditional boat builder built a big and a small wooden boat that where propelled with yulohs.

First we went out in a boat and they demonstrated the technique then after lunch we went to the boat builder who explained more about the boats.

Just when leaving Shigeatsu said something surprising: “The sea and the forest are sweethearts” Tomorrow we go to the mountains to plant trees. Do you like to come along? Fumio will be coming to, he added, and pointed to the boat builder, as an enticement.

We drove back to the oyster farm and had dinner; the day had gone quickly. They let me sleep in a nice room. We have to leave early tomorrow, as it’s a long way to the mountains, they said.

I asked them to wake me up.

I slept very well after finally after such a long search finally having found yuloh teachers.

I was woken by an embarrassed Kou, the English speaking son. We have to leave in five minutes but we come back to fetch you.

Later I understood that in Japan it was not polite to wake up a sleeping guest. Luckily years of singlehanded sailing had taught me to be a quick raiser.

Up in the mountains it was like a fair. People from all over Japan had come to help. Some people spoke good English and I was able to explain my interest in the yuloh. They offered me to stay as long as I liked and every evening I was welcome to come to the house for a meal and a talk, but during the day, they said we have to work hard.

One of the fishermen instructed me in the use of the little boat and I could use it as much as I liked during the days.

I stayed one month and learned many things from these friendly people.

Unfortunately the 2011 earthquake off the Pacific coast of Tōhoku completely destroyed the oyster farm.

Below are some pictures of my visit.