Click once or twice on the pictures to enlarge.

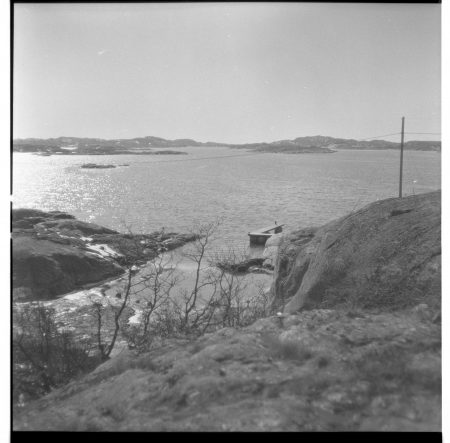

I was born on the windward side of Brännö a small island close to the North Sea on the Swedish west coast. Our house was 50 meters from the water.

A neighbor had a Bohuseka, a rowing pram. He told my mother that I could use it anytime I liked when I could swim 50 meters and tie a clove hitch. That was no problem and I was out on the water at a very early age. Although it did not have sails, that boat with its very shallow draft was the best plaything I ever had. There was plenty of surrounding islands, inhabited and uninhabited to discover. I thus got it into my blood that a boat without a deep thing hanging below could land most anywhere.

I was exploring and wandering around in my little craft. To wander is to move or go about aimlessly, without plan or fixed destination to ramble to roam.

To cruise is to travel without destination or purpose. Today few yachts cruise in that original sense of the word. They have even turned the ARC the Atlantic Rally for Cruisers has turned into a race.

Today boats are too big. They are like trains that take a long time to start and an equally long time to stop.

When I am out walking it is easy to stop and look at something.

When I are on my bicycle it is a bit more difficult but still very easy to stop when I see something interesting.

People that drive cars very seldom stops to look at something interesting it’s too much of a hassle.

For a passenger on an airplane it is not even possible to stop and look at something interesting.

What I mean with the above is that a small boat is very handy. You have good control over. It lets you that decide where to go and where to stop. Ocean going production boats are not small and they do not have shallow draft. You are not really longer the Captain; your big boat has become the master.

I build my own ocean going boats because production boats lack many of the properties I desire.

Among them is smallness and shallow draft. Its advantage starts in workshop. When I build I can stand on the shop flour and do most of the work from the outside. That saves much work as I can have my tools cart and do not have to climb down a ladder when I need something.

Building is one thing but you might ask: Is a small shallow draft boat seaworthy enough, because generally speaking the deeper draft a boat has the better it will perform.

As an aspiring yacht designer I had read much about Cape Horn. It had an awesome reputation. If I could round the Horn east to west in a small boat I would be able to answer yeas to that very important question.

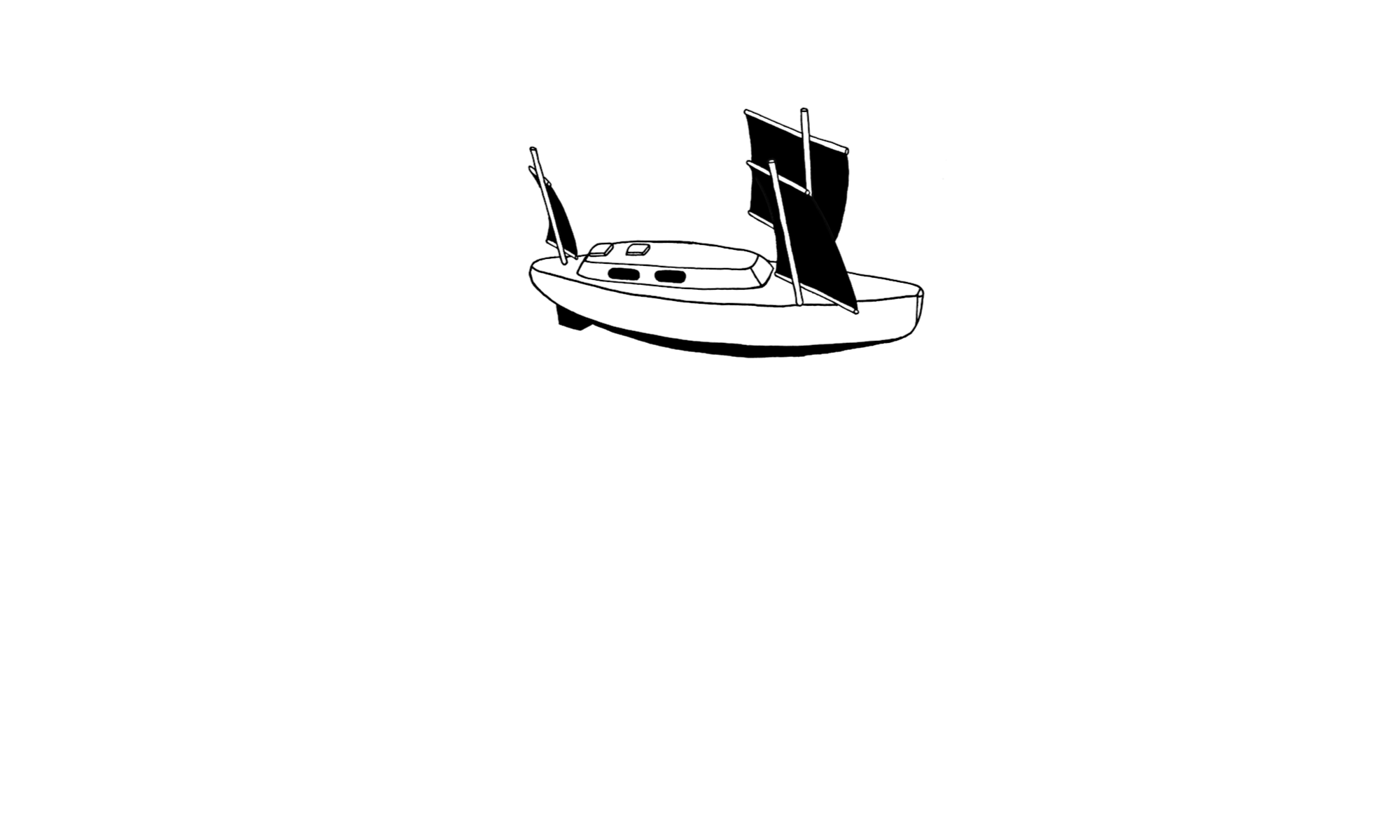

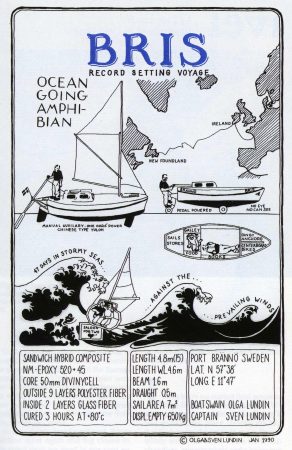

1974 I had tried the Horn in 20 feet long Bris a boat that I had built in my mother’s basement to get her out of the door she had was a narrow beam of 1.72 meter. To get her shallow draft I designed her with a centerboard. Her rigging was standing lugsail on two freestanding masts.

The constraint of the basement door caused other problems. First I built her hull cold molded. I then built the interior, deck and deckhouse attached with screws. To get her out I had to take her apart to reassemble her in the garden. Unfortunately there was lots of rain. The humidity made the wood damp. Gluing the deck and deckhouse went OK but the centerboard case I did not get right in those days before epoxy.

She leaked. I fixed the worst. Another problem was that the mast got too heavy. Most mast is supported. Today a few are freestanding. Those days they were rare. The sparmaker who was making them for me made them extra strong to stand up to the Cape Horn storms I was going to encounter. That was bad because that made them very heavy. I had already made extra heavy specifications. The masts ended up more than twice as strong as intended.

With a leaky and tender boat I started to sail south September 1974. In November I stopped in Holland to fix things but didn’t get very far without my tools.

I had very little money so I decided better be sure than sorrow and convert her to a conventional design. I went back to Sweden borrowed a car and a trailer and drove Bris back to my mothers house.

Out came the centerboard case. Reluctantly I installed a small ballast keel and converted the rigging to a Bermudan sloop with an aluminum mast supported by stays and shrouds.

Then I left again. This time even more determined, I sailed across the North Sea out between Orkney and Shetland.

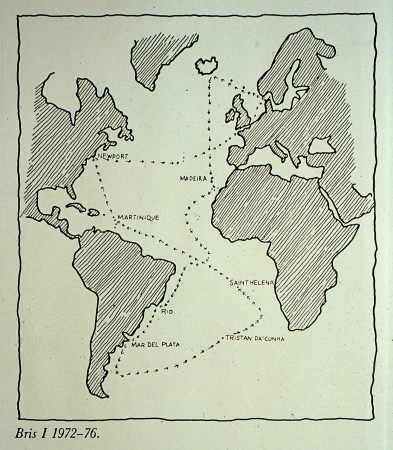

The weather across the North Sea had been very find but as soon as I came out into the Atlantic I was meet by a series of gales that I thought would never end. I drove my small boat against them as hard as I could. Finally after 45 days out of Norway I made a landfall on Funchal Madeira.

It was July 1973 and at the time I was the only cruiser in the harbor. From Madeira I sailed to Rio then to Mar del Plata in Argentina.

In early 1974 I headed south for Cape Horn. At first progress was good but then one wave capsized Bris, that came as something of a chock. My idea had been she would ride like a seagull on top of the waves.

There was a mess in the boat. Lots of water had entered her cabin and things had been thrown around. Still it could have been much worse. She was in good shape; most of the damage had been done to my and my boats pride.

I got rid of the water put things back in their place. More wise, I did as much preparation for bad weather I could with my limited means and kept sailing towards the Horn.

A week later, a sudden wind of hurricane force hit us. Sudden come, sudden go I thought. To my surprise the wind just kept increasing. I tied a tire to along rope and through it in the water to act as a drogue. It kept the stern of my little double ender against the storm.

Everything seemed to be fine despite the roaring wind. I relaxed and started to read a book on physics. Time passed everything was fine despite the raring wind and the heavy breakers that hit her like a hammer.

Then suddenly Bris pitch poled. She capsized stern over bow.

Sven, I heard Janneke scream.

“We are in heaven.”

I have not told you that in Holland I had met a girl with a vivid imagination. She had signed on. Anyway now she thought she was in heaven.

She was keen on classical music and had a cassette player. It had hit the ceiling and Bach music was streaming. That explained the trumpeting angels she thought she heard. I soon got her back to earth bailing.

Thanks to the preparations we had done since the capsize there was now less water and less mess in the boat.

Still enough was enough. I started to draw a new boat, but it was a long way to my mother’s basement and I had not any money either.

I saw a tiny dot on the pilot chart, Tristan da Cuhna. I did not know if it was possible to land there or if it was inhabited but it gave us a chance. We headed east with the prevailing westerlies.

After two months and many storms we made a landfall.

The island was inhabited. 293 persons lived there. There was no harbor but they had a landing place. Thanks to her small size Bris was lifted a shore the willing islanders who thought that we were shipwrecked. I told them that I was an aspiring yacht designer doing research on the seaworthiness of small boats in stormy seas.

Then you have come to the right place I was told.

I stayed on the island 4 months.

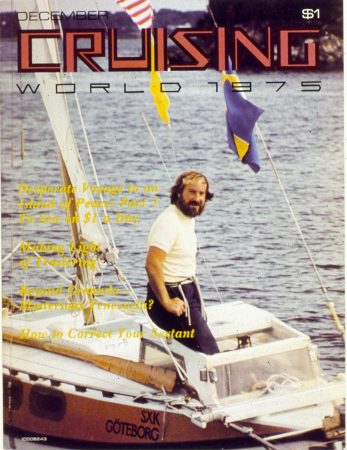

I cruised for some more years in Bris. I sailed up to the US started to write for Cruising World magazine and worked with trimaran designer Dick Newick for a year on Martha’s Vineyard. There I learned about epoxy and carbon fiber. 1976 I sailed Bris back to Sweden and started to build the next boat.

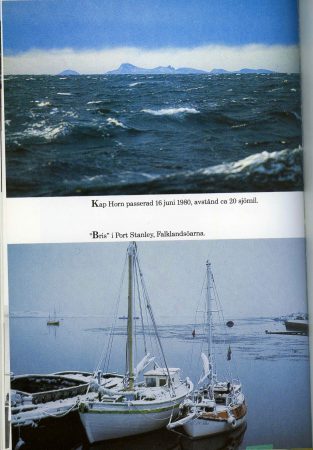

June 21st 1980, midwinters night, with a moon shining brightly, and a rare near calm, I entered Port Stanley after finally having rounded Cape Horn east to west in 19 feet Al-Bris.

The Falklands is a windy place. During the four months I cruised the islands, the wind speed reached one hundred knots on three occasions.

I had successfully rounded Cape Horn from east to west. It had been a cold dark voyage with much stormy weather.

I had not planned to do the passage in winter, but during the passage from Madeira to South America I had noticed a bulging area on my stomach. I had no idea of what it was, but it surely did not look healthy. At the yacht club in Mar del Plata, Argentina I asked a doctor.

It is inguinal hernia. He said.

Is it anything I should worry about? I asked.

If your intestine comes out through the abdominal wall it can be life threatening. He said.

I turned pale.

Don’t worry, he said, now you are in Argentina. We will help you. Coming all the way from Sweden in that tiny boat you are a hero to us.

A few weeks later I was at the hospital undergoing surgery.

I had worried about an Argentinian doctor operating on me but they were, all went well.

The problem started when I began to walk. It was painful.

That’s normal, The doctor said, after some time the pain will go away, but you have to wait at least a month before setting out towards Cape Horn.

My problem was that with all the waiting the good season summer was turning into winter and I had neither the money nor the patience to wait one more year. I was eager to find out what Cape Horn was about and I was confident in my little boats seaworthiness.

I cleared out in the month of May 1980.

Those days there was no alternative to astro or celest navigation. To find your position with a sextant in the trade winds were the sky is clear and the sun is up all day is a piece of cake once you have learned how to do the calculations.

The basic idea is that with the help of a sextant you measure the angle between the celest body and the horizon. An angle of more than 20° is most desirable.

In my case after leaving Mar del Plata it was much more difficult. The further south I sailed the less the sun rose above the horizon and the further north the sun mowed the less the sun rose above the horizon, a double effect.

Finally south of Cape Horn in June the sun did not rise more than 11° above the horizon at noon. This was aggravated by big waves and the wintry weather. Most of the days the sky was so overcast that it was impossible to get any observations at all.

A sextant is not some kind of old fashioned GPS. It is a precision instrument made to measure angles, nothing else. It does not give you your position but if you measure the angle between the sun and the horizon with an accuracy of minute of a degree you can then with the help of a nautical almanac and spherical trigonometry calculate your position line.

For those not familiar with celest navigation there is 60 minutes to a degree. That’s how precise you have to measure the angle from a rolling boat in heavy weather.

It is imperative that that measurement is taken vertically, at right angle to the horizon, that is right below the sun. If you hold the instrument at an angle you get a reading that is too big. To eliminate that error you swing the sextant back and forth a few times using the sun as the center.

That trick must be done at that very short moment you are at the crest of the wave otherwise you do not get a true horizon.

In overcast weather sometimes I had to be on deck sextant in hand for a long time to get a glimpse of the sun.

Obviously I could not use gloves when adjusting the instrument to get the correct reading so my hands got cold. When I finally got an observation I had to write down the time to the second. For safety I always took a series of reading and averaged them.

One observation gives one line of position at right angle to the sun. Somewhere along that line you are. To determine where on that line you are you have to take a second observation of the sun after a few hoers when its bearing or azimuth has mowed preferable 90°. Where the two lines cross there are you. If you have moved you must make a running fix. If you are a good navigator and make no errors you can with this method if the weather is OK usually get your position within 3 miles after a few hoers obviously in my case there near Cape Horn I had to calculate with a much higher degree of accuracy.

One more problem I had was that the sun rose and set at about the same place as it does at high latitudes in the winter. The two lines of position was therefore nearly parallel and the fix even more unreliable.

To do those observations and the calculations correct was for me a matter of life and death. I would not have survived a shipwreck on the coast near Cape Horn in the winter, probably not even in the summer.

Why did I tell you all this about how difficult it was to navigate with the sextant?

Unknown to many Cape Horn is not the most southerly part of South America. The most southerly part is the Diego Ramirez Islands, about 60 miles southwest of Cape Horn. I was in danger of being shipwrecked on those island.

At the time of my rounding there was a conflict between Argentina and Chile over some Antarctic islands and all lighthouses were shut down.

There are strong unreliable currents in the area and I did not feel sure of my position.

There are bold pilots and there are old pilots, but there are no old bold pilots, the saying goes.

I am a prudent navigator. I was happy to have rounded Cape Horn from east to west.

I had already experienced more of the stormy Cape Horn conditions than I needed to design small seaworthy boats. It was important that I came back alive to tell the story and design more boats.

Once again I decided enough is enough. So after having taken a few pictures of Cape Horn in a rare moment of clear sight I sailed some extra miles west just to make sure, then I turned and headed east south of Isla des Estados and then for the Falkland Island.

I had designed Al-Bris with deep draft to make her able to stand up to the frequent Cap Horn gales. Now in the Falklands I had problems finding a calm anchorage.

There were protected creeks and sheltered places that dried out a low tide. Those places would have been a perfect place for my boat if only she did not have so deep draft. In consequence I had to suffer discomfort but I had learned some good lessons.

On my next boat, the 15-feet long Amfibie-Bris the problem of draft was solved with a centerboard. I placed it forward of her mast and used the rudder as second lateral area. With the help of that innovation it did not to interfere with the cabin space.

By pure luck I had found a new girl. We had transported Bris on a trailer behind a car to La Trinite sur Mer in Brittany and cruised the area for some time.

On 22 April 1989 we left Le Croisic. It was my 50th birthday I had planned to eat some ice cream as a celebration that day but the weather was fantastic so left we did.

We sailed to Baltimore close to the famous Fastnet Lighthouse on the Irish south west coast. It’s a rather small fishing harbor and visiting yachts mostly have to anchor outside on the roadstead. A gale was announced and as Bris had a strong flat bottom and shallow draft, now unlike on the Falkland Islands there was an alternative. A quarter of a mile southwest of the fishing harbor is cove, aptly named The Cove it was a fantastic place with a nice sandy beach. We went there at high tide, waited for the water to ebb and walked out the anchor. A day later the gale came up the other yachts with deep draft had less than comfortable nights on the open roadstead.

The Cove was a convenient place to fill up Bris stores before we sailed towards Newfoundland our destination.

But can a 15-feet centerboard go to windward out on the deep ocean? Crossing the Northern North Atlantic Ocean against the prevailing westerlies?

Glad you asked.

We did very well. At one time there was a series of gales that lasted for 11 days.

Also this was voyage was done before the advent of GPS. When the weather had moderated and I got out my sextant we were further west than we had been when the gales had started.

The customs in St Johns was not too pleased with our landfall. They told me that I was irresponsible, that their waves were too big for my boat.

Cheeky I told them that compared to the Cape Horn waves that I had experienced their waves were just blah.

That infuriated them. The result was that they put a red stamp in my ships paper saying that Bris was seized.

My boats small size had angered the Canadian custom men and caused trouble. Now her small size, her centerboard and shallow draft offered me a way out of a tricky situation.

While the custom men watched St Johns only harbor entrance so that I would not leave. I rented a U-Haul truck, put my boat into her and drove to the US.

At the US/Canadian border the custom employees asked if I had furniture in the truck.

It is the smallest boat ever to have crossed the Northern North Atlantic against the prevailing westerlies.

Is it a record? The officer asked friendly.

Yes Sir it’s a record. I answered.

He saluted and I was in the land of freedom with my dear little boat.

Up in St Johns the customs used to big cargo boats probably are still trying to figure out how their seized boat could have disappeared without them noticing it.

A small boat and shallow draft solves many a problem.

Go small, go shallow draft and live a simple, sustainable life.